One day last fall, a young Israeli woman named Sharon went with her fiancé to the

Sharon is a small woman in her late 30s with shoulder-length brown hair. For privacy’s sake, she prefers to be identified by only her first name. She grew up on a kibbutz when kids were still raised in communal children’s houses. She has two brothers who served in Israeli combat units. She loved the green and quiet of the kibbutz but was bored, and after her own military service she moved to the big city, which is the standard kibbutz story. Now she is a Tel Aviv professional with a master’s degree, a job with a major H.M.O. and a partner — when this story starts, a fiancé — who is “in computers.”

This stereotypical biography did not help her any more at the rabbinate than the line on her birth certificate listing her nationality as Jewish. Proving you are Jewish to Israel’s state rabbinate can be difficult, it turns out, especially if you came to Israel from the United States — or, as in Sharon’s case, if your mother did.

In recent years, the state’s Chief Rabbinate and its branches in each Israeli city have adopted an institutional attitude of skepticism toward the Jewish identity of those who enter its doors. And the type of proof that the rabbinate prefers is peculiarly unsuited to Jewish life in the United States. The Israeli government seeks the political and financial support of American Jewry. It welcomes American Jewish immigrants. Yet the rabbinate, one arm of the state, increasingly treats American Jews as doubtful cases: not Jewish until proved so.

More than any other issue, the question of Who is a Jew? has repeatedly roiled relations between Israel and American Jewry. Psychologically, it is an argument over who belongs to the family. In the past, the casus belli was conversion: Would the Law of Return, which grants automatic citizenship to any Jew coming to Israel, apply to those converted to Judaism by non-Orthodox rabbis? Now, as Sharon’s experience indicates, the status of Jews by birth is in question. Equally important, the dividing line is no longer between Orthodox and non-Orthodox. The rabbinate’s handling of the issue has placed it on one side of an ideological fissure within Orthodox Judaism itself, between those concerned with making sure no stranger enters the gates and those who fear leaving sisters and brothers outside.

Seth Farber is an American-born Orthodox rabbi whose organization — Itim, the Jewish Life Information Center — helps Israelis navigate the rabbinic bureaucracy. He explained to me recently that the rabbinate’s standards of proof are now stricter than ever, and stricter than most American Jews realize. Referring to the Jewish federations, the central communal and philanthropic organizations of American Jewry, he said, “Eighty percent of federation leaders probably wouldn’t be able to reach the bar.” To assist people like Sharon, Farber has become a genealogical sleuth. He is the first to warn, though, that solving individual cases cannot solve a deeper crisis.

Judaism, traditionally, is matrilineal: every child of a Jewish mother is automatically considered a Jew. Zvi Zohar, a professor of law and Jewish studies at Bar-Ilan University, told me that in Judaism’s classical view of itself, Jews are best understood as a “large extended family” that accepted a covenant with God. Those who didn’t practice the faith remained part of the family, even if traditionally they were regarded as black sheep. Converts were adopted members of the clan. Today the meaning of being Jewish is disputed — a faith? a nationality? — but in Israeli society the principle of matrilineal descent remains widely accepted. Sharon’s mother was Jewish, so Sharon knew that she was, too. And yet it seemed impossible to provide evidence that would persuade the rabbinate.

Sharon left the office infuriated. Her mother was Jewish enough to leave affluent America for Israel; her brothers had fought for the Jewish state. Now, she felt, she was being told, “For that you’re good enough, but to be considered Jews for religious purposes you’re not.”

Sharon’s mother, Suzie, is 66, a dance therapist, even tinier than her daughter, a flurry of movement in the living room of her kibbutz bungalow. Suzie’s maternal grandfather, David Ludmersky, was born in Kiev. When he was drafted into the czar’s army, he deserted, fled to America and worked to send a ticket to Rose, the girl he left behind. The Merskys (an Ellis Island clerk shortened the name) moved to the small Wisconsin town of Wausau, where their daughter, Belle (Suzie’s mother), was born. Suzie has heard that they didn’t like the place, that they consulted a fortuneteller, that she told them to move west to Minneapolis. There David Mersky indeed made his fortune, working his way from peddling fruit to owning one of the city’s first supermarkets.

I recount this family history because of its pure American Jewish normality. In Minneapolis, Belle Mersky married Julius Goldstein in a Conservative ceremony. This, too, was typical: Conservative Judaism was the common choice for American Jews leaning toward tradition. Julius’s brother became a Conservative rabbi. Belle and Julius raised their family on Minneapolis’s North Side, “a totally Jewish neighborhood then,” Suzie recalled. She went to Sunday school at Beth El Synagogue, a Conservative congregation.

Suzie began college at the cusp of the 1960s, attending the University of Minnesota, rooming with a friend from a Zionist summer camp. Her uncle, the Conservative rabbi, paid for her to go to Israel one summer on a student tour. When she returned to Israel after graduation, even the motor-scooter accident was practically part of the standard restless-youth experience. She broke her foot, put off her plan to join a dance company and took a room in a Tel Aviv rooming house. “I was sitting there with my foot up, crutches in the corner, and this handsome guy came in,” she told me. He was British. He and his best friend were living in Holland, “wanted to go somewhere” and drove overland to Israel.

“He ended up being my husband,” Suzie said with a laugh. He wasn’t Jewish, a twist in the story line. They left Israel together to wander through Europe and married in a civil ceremony in England. Those details would later loom immense: Had he been Jewish, had they married in Israel, she would have had a ketuba, or religious marriage contract issued by the rabbinate, for her daughter to show years later. In the excitement after Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War in 1967, they decided to return to the country. “He always wanted to live here,” she said, and “we were adventurous.”

Fast forward: Sharon, on her 38th birthday, took the day off from work to make wedding arrangements. First stop was the Tel Aviv Rabbinical Court.

The rabbinic courts are an arm of the Israeli justice system. Formally, the judges — rabbis with special training — are appointed on professional grounds. In practice, positions in the courts and in the state rabbinate are parceled out as patronage by religious political parties. The main function of the rabbinic courts is divorce, also a purely religious process in Israel. A secondary function is providing judicial rulings on whether a person is Jewish. For that, the main clientele is immigrants from the former Soviet Union. A fairly standard procedure exists for them. It includes examining Soviet-era documents, like birth certificates, that list a citizen’s nationality. (In the Soviet system, “Jewish” was a nationality, parallel to “Russian” or “Uzbek,” listed in everyone’s official papers.)

At the court, Sharon told me, the clerk who opened her file told her to bring her mother’s birth certificate and her parents’ marriage certificate. “I said: ‘But my mother’s birth certificate doesn’t say “Jewish.” It’s from the United States. They don’t write that. And the marriage license — they had a civil wedding.’ ” After she waited hours to see a judge, he told Sharon to return with “any document that would testify to her mother’s Jewishness.” She asked a court official if a letter from a Conservative rabbi would solve the problem. Her mother has a cousin in Florida who is a rabbi, son of the uncle who originally sent Suzie to Israel. No, the official said, “that won’t help. It has to be someone Orthodox.”

“When Sharon called me, she was crying,” Suzie told me. Her daughter said the court wanted testimony from an Orthodox rabbi who had known Suzie all her life. “Even if there was such a thing, he would be dead by now,” Suzie said. Lacking an official document labeling her a Jew and without a childhood connection to Orthodoxy, Suzie was again a typical American Jew. Nonetheless, she got on the phone. Her cousin in Florida told her to phone a colleague from Israel’s small movement for Conservative Judaism. He, in turn, said Seth Farber would help her. He was right.

Since genealogy is basic to this story, I will point out that Seth Farber’s great-great-great-grandfather was the pre-eminent Central European rabbi Moshe Schreiber, father of ultra-Orthodoxy. My guess is that Rabbi Schreiber would be confused by Farber’s approach to religion. Better known as the Hatam Sofer, or Seal of the Scribe, the name of his work of religious scholarship, he bitterly opposed fitting Judaism to modernity and was known for his principle, “Anything new is forbidden by the Torah.” An iconic portrait shows him with a long gray beard and a fur hat.

Farber, 41, has a round, clean-shaven face and frameless glasses that make him look like an earnest grad student. He grew up in Riverdale, N.Y., attending the kind of Orthodox parochial school that, he told me, “celebrated Americanism,” that turned the American bicentennial into the focus of an entire school year. In college, he maintained that balance of Orthodoxy and integration by cycling the length of Manhattan twice daily: mornings studying Talmud at Yeshiva University on 185th Street, afternoons at New York University for philosophy. He could have done his secular studies as well at the Orthodox university, he said, but he wanted “to understand the broad world, to meet non-Jews, to be exposed to broad ideas” — in short, to span the moat between traditional Judaism and modernity that his ancestor devoted his life to digging.

Farber was ordained as a rabbi at Yeshiva University, and in the mid-90s he moved to Israel. He completed a doctorate at Hebrew University in American Jewish history and started his own synagogue. It was the kind of place that ran a Passover charity drive, collecting the leavened food that religious Jews would normally throw away before the holiday and donating it to a welfare society in the Palestinian town of Bethlehem. He also got permission from the state rabbinate to perform weddings.

His organization, Itim, was born of a hike that he and his wife, Michelle, took in a barren gorge through the Judean desert. When they arrived at the gorge, they found they would need ropes to descend the cliffs into the freezing pools along the bottom, and another couple offered to share equipment. Along the way, their hiking companions said they weren’t married because “they couldn’t find a rabbi they could relate to.” Most secular Israelis imagine a rabbi looking more like the Hatam Sofer than the hiker in soaked shorts who offered to perform the ceremony. At the wedding, as nearly the only Orthodox Jew among 600 people, Farber said he began to understand how “disenfranchised” many Jews in Israel feel when dealing with state-run religion.

He decided to “create a place where the representatives of Judaism” aren’t government clerks. Itim distributes booklets that explain to Israelis how to arrange a circumcision, marriage or funeral. It helps secular couples find rabbis sensitive to their desires for their ceremonies. For the last five years, it has run a hot line for Israelis who face trouble in the rabbinic bureaucracy. Early on, Farber began receiving calls from people unable to prove they were Jews. Many were immigrants from the former Soviet Union, but some were Americans. Even a letter from an Orthodox rabbi didn’t always help. The state rabbinate no longer trusts all Orthodox rabbis.

Trust — or lack of it — is the crux. Zvi Zohar of Bar-Ilan University explained to me that historically, if someone said he was a Jew, “if he lived among us, was a partner in our society and said he was one of us, we assumed he was right.” Trust was the default position. One reason was that Jews were a persecuted people; no one would claim to belong unless she really did. The leading ultra-Orthodox rabbi in Israel in the years before and after the state was established, Avraham Yeshayahu Karlitz (known as the Hazon Ish, the name of his magnum opus on religious law), held the classical position. If someone arrived from another country claiming to be Jewish, he should be allowed to marry another Jew, “even if nothing is known of his family,” Karlitz wrote.

Several trends have combined to change that. In an era of intermarriage, denominational disputes and secularization, Jews have ceased agreeing on who belongs to the family, or on what the word “Jew” means. Ultra-Orthodox Jews increasingly question the Jewishness of those outside their own intensely religious communities. The flood of immigrants from the former Soviet Union to Israel deepened their doubts. In the Soviet Union, when someone with parents of two nationalities received identity papers at age 16, he could pick which nationality to list. A child of a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother could put down “Jew.” The religious principle of matrilineal descent was irrelevant.

In the United States, the Reform movement responded to rising intermarriage by deciding in 1983 to accept children of a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother as Jews if they were raised within the faith. The denominations also diverge on how to accept a convert into Judaism. Orthodox Jews generally do not regard conversions by non-Orthodox rabbis as valid — either because the rabbis do not strictly follow religious law or because they do not require the converts to do so. The number of people in America “recognized by some movements as Jewish but not by others” is “certainly in six figures,” according to Jonathan D. Sarna, a Brandeis University professor and the author of “American Judaism: A History.”

Denominational rules are only part of the story. In much of the world, Jewish identity has become fluid, part ethnicity, part religion, a matter of choice. “In the United States and also in Western Europe there are many kinds of Jews,” Prof. Menachem Friedman, a Bar-Ilan University sociologist of religion, told me. “People can change religions and identities quickly.” But in Israel, belonging has practical consequences: The 1950 Law of Return grants every Jew the right to immigration. In 1970, the Knesset defined the term “Jew” as meaning “one who was born to a Jewish mother or who converted to Judaism.” That was a partial victory for those demanding traditional religious criteria. But to keep the door open to those who didn’t fit that definition, the amendment also granted the right of immigration to the child, grandchild or spouse of a Jew. Each time religious parties sought to go further and define conversion by Orthodox rules, Sarna recounts, “American Jewry would go into crisis mode,” its leaders insisting that Israel couldn’t delegitimize the non-Orthodox denominations.

In 1986, the Israeli Supreme Court ordered the Interior Ministry’s Population Registry to list Shoshana Miller, a Reform convert from America, as Jewish on her ID card. The ultra-Orthodox interior minister resigned in protest. In practice, though, the rabbinate paid scant attention to ID cards. Couples registering to marry were asked to bring two witnesses who could testify that the applicants were Jews under Orthodox law. The two arms of the state, secular and religious, operated according to separate rules.

And in the rabbinate, power was shifting to the ultra-Orthodox — the wing of Judaism that segregates itself from the surrounding society and culture. In the early years of the state, those serving in the rabbinate generally identified with the project of building a Jewish state and felt a connection with secular Jews. Politics changed that. Thirty years ago, ultra-Orthodox parties held 5 of the 120 seats in the Knesset. Today, they hold 18. Secular politicians need their support to build a stable coalition government. One way to gain it is to back ultra-Orthodox candidates for rabbinic posts. It is one of the stranger alliances that politics can create: the secular politicians regard “Jewish” mainly as a nationality, an ethnic identity that includes both believers and nonbelievers. For the rabbis they have empowered, “Jewish” is exclusively a religious category, and secular Jews are at best estranged cousins.

The true Era of Mistrust began in the 1990s, with the exodus of Jews from the Soviet Union. A semiclandestine agency called Nativ (Route) was responsible for checking whether would-be immigrants qualified under the Law of Return. To establish Jewish identity, the agency scrutinized Soviet documents.

At the state rabbinate, marriage registrars adopted their own policy of doubt. Increasingly, rabbinate clerks sent anyone not born in Israel, or whose parents weren’t married in Israel, to a rabbinic court to prove that he or she was Jewish. Rabbi Osher Ehrentreu, the official at the rabbinic courts responsible for checking Jewish status, can’t name a date for the change, which apparently emerged without an explicit decision. The courts sought the same kind of documents as Nativ did, like birth certificates of the applicant’s mother and maternal grandmother listing them as Jews.

The traditional willingness to trust a person who said he was Jewish, Ehrentreu asserts, presumed that no one had anything to gain by it. Today, he told me, there are ulterior motives — to be able to leave another country and come to Israel, “to be recognized here as Jewish, to be able to get married.” That is, Israel’s prosperity, its attractiveness to immigrants, is now a reason for doubt.

Friedman, the reigning academic expert on ultra-Orthodox society in Israel, suggests that the deeper reasons for doubt are difficult for the rabbis to articulate. In contrast to Orthodox Jews like Farber, the ultra-Orthodox have little sense of risk that by raising doubts they might exclude a person who is really Jewish. “If you don’t keep the Torah and the commandments, O.K., so I excluded you. In any case you weren’t a complete Jew,” is how Friedman explains the attitude.

The policy of suspicion is applied to all immigrants. Rabbi Rasson Arussi, chairman of the Chief Rabbinate’s committee on marriage, told me that “populations where there is doubt about Jewishness” include those from Western countries, specifically “the sectors connected to Reform Jews.” The rabbinate’s expectations, however, are a poor fit with the United States. American Jews generally don’t have government papers testifying to their Jewishness. While a British Jew might turn to his country’s chief rabbinate for certification that he is Jewish, the very idea of a chief rabbi sounds outlandish in the United States.

And as Farber points out, the reign of doubt at the Israeli rabbinate began as it was becoming steadily less likely that an American Jew would be able to dig an Orthodox marriage contract out of her mother’s drawer. In the generation after World War II, most American Jews moved away from even a nominal connection to Orthodoxy. Today, young American-born Jews are likely to be two or three generations removed from any tie with Orthodoxy.

Strikingly, the rabbinate’s doubts extend even to Orthodox rabbis in America. “They’re not familiar with them,” Friedman told me. “They say: ‘The rabbis in the United States, in England, aren’t the kind we know. Someone can define himself as an Orthodox rabbi, but really he’s Reform.’ ” A marriage registrar given a letter from an Orthodox rabbi abroad certifying that a person is Jewish is now expected to check with the office of Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar, which maintains a list of diaspora clergy whose letters are to be trusted. The list is not publicly available. If the rabbi who wrote the letter is not on the list, the applicant is asked for other proof or referred to the rabbinic courts.

Converts, even the children of converts, potentially face greater difficulties, because the rabbinate has also become more skeptical about Orthodox conversions performed abroad. What’s more, under pressure from Chief Rabbi Amar, the main association of Orthodox clergy in the United States, the Rabbinical Council of America, is establishing its own regional rabbinic courts for conversion. A recent council position paper warns that the group makes no commitment to stand behind conversions performed by other rabbis. The paper also stresses that converts are expected to accept Orthodox religious law, or Halakhah.

The policy has divided the American group. Advocates say that standardization will ensure that converts are accepted by all religious Jews. A former council president, Marc Angel, a sharp critic, told me the group “decided to capitulate” to Amar and robbed individual rabbis of their prerogative to measure the needs and commitment of prospective converts. “The rabbinate in Israel has put the Orthodox rabbinate” — meaning Orthodox rabbis in the United States — “on the same level as Reform rabbis,” Angel said. He now advocates a position once unthinkable among R.C.A. rabbis: Israel would be better off if it instituted civil marriage and cut the state’s ties with the rabbinate.

Not surprisingly, leaders of non-Orthodox denominations in the United States sound both pained and vindicated when discussing the rabbinate’s policies. “There is quite an irony in this,” Rabbi Eric H. Yoffie, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, told me. In the past, “Orthodox authorities in America have basically defended the system, and they’ve embraced this religious monopoly as being important and necessary, thinking all the while that it was directed primarily against us, us meaning the non-Orthodox community.” Now their own bona fides are in doubt.

Arnold M. Eisen, chancellor of the American Conservative movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary, stresses the damage to Israel-diaspora relations: “All the data shows a growing rift between American Jews and Israeli Jews, and the younger you are as an American Jew, the less that you care about the state of Israel. This is just terrible. And one of the reasons for it — not the only reason, but one of the reasons for it — is this kind of insulting treatment of the majority of American Jews by the Israeli rabbinate.”

Seth Farber, a pragmatic idealist, does not expect either the rabbinate or the basic disagreements about who is Jewish to disappear. What he rather desperately believes, he said, is that “a conversation has to begin” on how Orthodox Jews — including the rabbinate — and non-Orthodox Jews can agree “to trust each other” despite the disputes. The Israeli rabbinate, that is, should trust a Reform rabbi’s testimony that a person’s mother is Jewish. For Farber, there is a price to overwhelming doubt: It means “writing thousands of people, if not hundreds of thousands, out of the Jewish world.”

With no grand compromise in the offing, Farber works on individual cases. Over the last five years, he said, he helped more than 100 people prove to the rabbinate that they were Jewish. The amount of detective work he undertakes demonstrates his own dedication. But it also shows how difficult it can be for people from typical American Jewish backgrounds to provide evidence of an identity they regard as self-evident.

Mark Rashkow, whose wedding was saved by Farber’s intervention, described him as “relentless.” Rashkow came to Israel from Chicago in 2003 to woo the woman he loved as a young volunteer 30 years before at Kibbutz Hazorea. Both he and she were at the end of long marriages. A year later, just days before their wedding, the local rabbinate informed him that he had yet to show he was Jewish. A rabbinate official in the town of Afula, near Hazorea, dismissed a letter from his Conservative rabbi in America, saying, according to Rashkow: “It doesn’t interest me. He’s a goy.”

Growing up in Chicago, Rashkow said, “I thought my first name was ‘kike’ until I was 12.” But when he found Farber via an Internet search just a few days before his planned wedding, the only leads Rashkow could provide him with were his maternal grandmother’s name and her approximate year of death. “Seth Farber, to me, was like an angel sent from heaven,” said Rashkow, who told his story at an exuberant pace. Farber began phoning Jewish cemeteries, working late into the Israeli night to reach Chicago in daytime. On the fourth or fifth call, he succeeded: the voice at the other end had the name listed in a section of the graveyard belonging to a society of Jews who’d come from Sokolow, in Poland. A cemetery employee sent pictures by e-mail of the gravestone, which was replete with Hebrew.

The next step was finding a birth certificate for Rashkow that showed his mother’s name, and one for his mother that listed her mother — thereby establishing his link to the gravestone. A lawyer whom Rashkow knew in Chicago rushed to the courthouse to get the papers. Farber then contacted the Chicago Rabbinical Council, an Orthodox body recognized by the Israeli rabbinate, to certify Rashkow as Jewish. The faxed letter arrived a day before the wedding, and Rashkow was able to marry the woman he had dreamed of for 30 years.

Suzie, Sharon’s mother, called Farber on a Sunday morning, the start of the Israeli workweek. He asked her for her grandmother’s maiden name, which she didn’t recall, and told her to ask someone in Minnesota to find her maternal grandparents’ tombstones.

“The hunt is on,” he wrote me in an e-mail message that night. He contacted the Chicago Rabbinical Council, which provided the names of the rabbi of an Orthodox synagogue in Minneapolis and his predecessor. Farber called both. Neither knew Suzie’s family, and the synagogue had no record of her grandmother. An old friend of Suzie’s in Minneapolis went to the courthouse and got a copy of her parents’ marriage license, signed by a rabbi. Farber did a Google search for his name and found that he had been a leading figure in the Conservative movement — meaning the license was at best weak supporting evidence before an Israeli rabbinic court. Once again, the link to an Orthodox community was missing.

Farber went to the Web site of Ellis Island and ran searches for Suzie’s family members in the repository of records of the “teeming masses” that arrived there. The manifests of arriving ships list “race or people” of immigrants, and “Hebrew” — meaning Jew — is one designation. But he was unable to locate any record of Suzie’s grandmother. “I’m a little less confident than I was,” he told me on the third day of his hunt.

Online, he found the Portage County Historical Society of Wisconsin. He sent the group an e-mail message about Suzie’s mother, born as Belle Mersky in 1907, asking “if, by any chance, there might be synagogue records of her birth available to you.” It was a geographical near miss; Wausau is in neighboring Marathon County. His message was forwarded to Rabbi Dan Danson of Wausau’s sole synagogue, a Reform congregation. But it had no archives of births from before 1988. Another dead end.

By now, though, Farber had phoned the Marathon County Register of Deeds, seeking Suzie’s mother’s birth certificate. The request, he was told, had to come from an immediate relative. Fortunately, Danson offered to help, and Suzie sent him the necessary information by e-mail. By Friday morning — five days after Suzie first called Farber — Danson was at the Wausau courthouse with the papers and $20 of his own money. Belle Mersky’s birth certificate, faxed to Farber’s home, showed that her mother’s maiden name was Rose Reuben.

Suzie’s niece visited the Jewish cemetery in Minneapolis where her grandparents were buried. The tombstones, originally placed flush with the ground, were now covered with grass and sod. She went home, returned with a shovel, and uncovered the evidence. In the photo of the gravestone that she sent by e-mail, above the name Rose Mersky in English was Hebrew: “Rachel, daughter of Moshe,” with the date of death, the sixth day of the Hebrew month of Elul, in the year 5714 (1954).

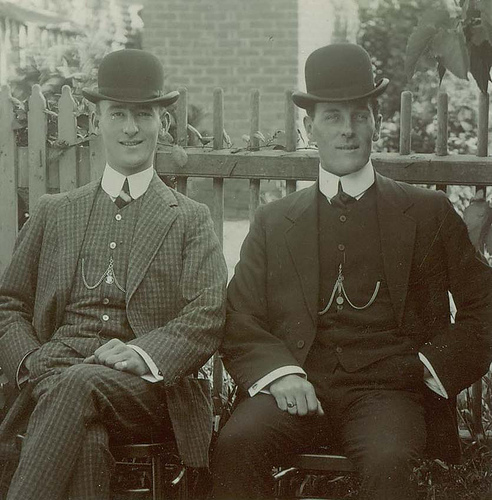

A week into the search, evidence was coming together. In a school project her son once did, Suzie found a family photo of her grandmother’s grandfather, Mikhael Ludmersky, an archetypal 19th-century Eastern European Jew with a white beard and black cap. From her family’s Conservative congregation in Minneapolis she received yahrzeit cards for her grandparents — records used to remind relatives of the anniversaries of their loved ones’ deaths, when the kaddish prayer should be recited. Even given the source, it was supporting evidence.

Farber arrived at the Tel Aviv Rabbinical Court about two weeks after Sharon’s first visit. He’d called and arranged with a judge to be squeezed in before the day’s docket of divorces. He had power of attorney, so Sharon didn’t need to appear. He wore a black suit and a gold tie, and his face was narrow and taut. “Now I’ve moved up from detective to lawyer,” he said. He was ushered into a tiny courtroom, where three rabbis, dressed in the black coats of the ultra-Orthodox, sat at a raised bench. Farber approached and made his case to one. He showed the series of birth certificates of Sharon’s maternal line, with the surnames Goldstein, Mersky, Reuben. “These are all clearly Jewish names,” he said. He presented the picture of the tombstone of Rachel, daughter of Moshe, and the photograph of Mikhael Ludmersky in his black cap, and the rest of his exhibits. The judge said to wait outside.

Twenty minutes later, a clerk called Farber in and presented him with a one-sentence judgment stating that Sharon is a Jew.